A song for spring, redistributing beauty, PKD's problems with progress.

Some book reporting on Wagner, Philip K. Dick and Svetlana Alexievich.

IN THE BEGINNING

I’m in my second round of a book club with The Catherine Project, which hosts free, online reading groups focused on the classics. (If you’re looking for a book club, I’ve found this to be really enjoyable, with a close focus on the reading and minimal tangents. They have their summer courses out now, registration ends April 8th.)

For this one, we’re reading Richard Wagner’s Ring Cycle together as a text. The prelude to the first opera, Das Rheingold, is the perfect song for spring, like earth coming to life again after a hard frost or the start of the universe, in Genesis.

There’s a bit of Louise Gluck’s poem the Wild Iris here:

“You who do not remember passage from the other world/I tell you I could speak again: whatever/returns from oblivion returns/to find a voice.”

There’s also an overlap between Wagner and Michel de Montaigne, the subject of my last Catherine Project group (I’ve found that everything somehow overlaps with Montaigne.) In the second of the operas, Die Walkure, Wotan (maybe more familiar to us as Odin) laments his inability to forge an equal:

“To my loathing I find/ only ever myself/ in all that I encompass!/ That other self for which I yearn,/ That other self I never see;/For the free man has to fashion/himself/serfs are all I can shape.”

This aligns well with Montaigne's essay on the downsides to being high-born. He argues that a man in a position of power will never get anyone to fight him fairly, a bleak and isolating proposition:

“‘Tis pity a man should be so potent that all things must give way to him; fortune therein sets you too remote from society, and places you in too great a solitude. This easiness and mean facility of making all things bow under you, is an enemy to all sorts of pleasure: ’tis to slide, not to go; ’tis to sleep, and not to live.”

There’s a reason kings tend to relish equestrianism, says Montaigne. Horses are uninterested in human power dynamics and will happily buck off any kind of man!

REDISTRIBUTING BEAUTY

I’ve just finished Svetlana Alexievich’s Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets, an oral history collection of those who lived through the fall of communism in Russia. It’s an immense read. Whether you’re an enthusiast of communism, or an ardent opponent, you’ll find yourself with some sympathy for the other side in these stories, which is maybe why it’s so compelling a read.

There are many things which have stuck with me. One was the account of Vasily Petrovich N., a member of the Communist Party for nearly 70 years. His dedication to the party was incredible.

Despite both being party members in perfect standing, his wife is thrown into a Gulag. At first, Vasily think this may have been because he inadvertently sat down too early at a party meeting, after a speech praising Stalin launched a 30 minute standing ovation. It’s actually because she corresponded innocuously with her sister in Poland. A neighbor had informed on her (a pattern you’ll notice in Secondhand Time).

Vasily is also imprisoned, interrogated and tortured. When released, he volunteers for the front in the hopes of getting back in the Party’s good graces. When he returns from war, he’s told his wife has died in prison, but he can rejoin the Party: “They handed me back my Party membership card. And I was so happy! I was so happy.”

Alexievich, in a rare instance in which she records her own reaction during an interview, tells him she could never understand this sentiment. He replies:

“You can’t judge us according to logic. You accountants! You have to understand! You can only judge us according to the laws of religion. Faith! Our faith will make you jealous! What greatness do you have in your life? You have nothing. Just comfort. Anything for a full belly…those stomachs of yours…Stuff your face and fill your house with tchotchkes. But I…my generation…We built everything you have.”

There’s much insight here. Many are bewildered by the enduring appeal of communism, despite its track record of mass death, displacement, suppression of dissent and absurd levels of social control, forgetting that communism also offers a profound religious experience for many of those who believe.

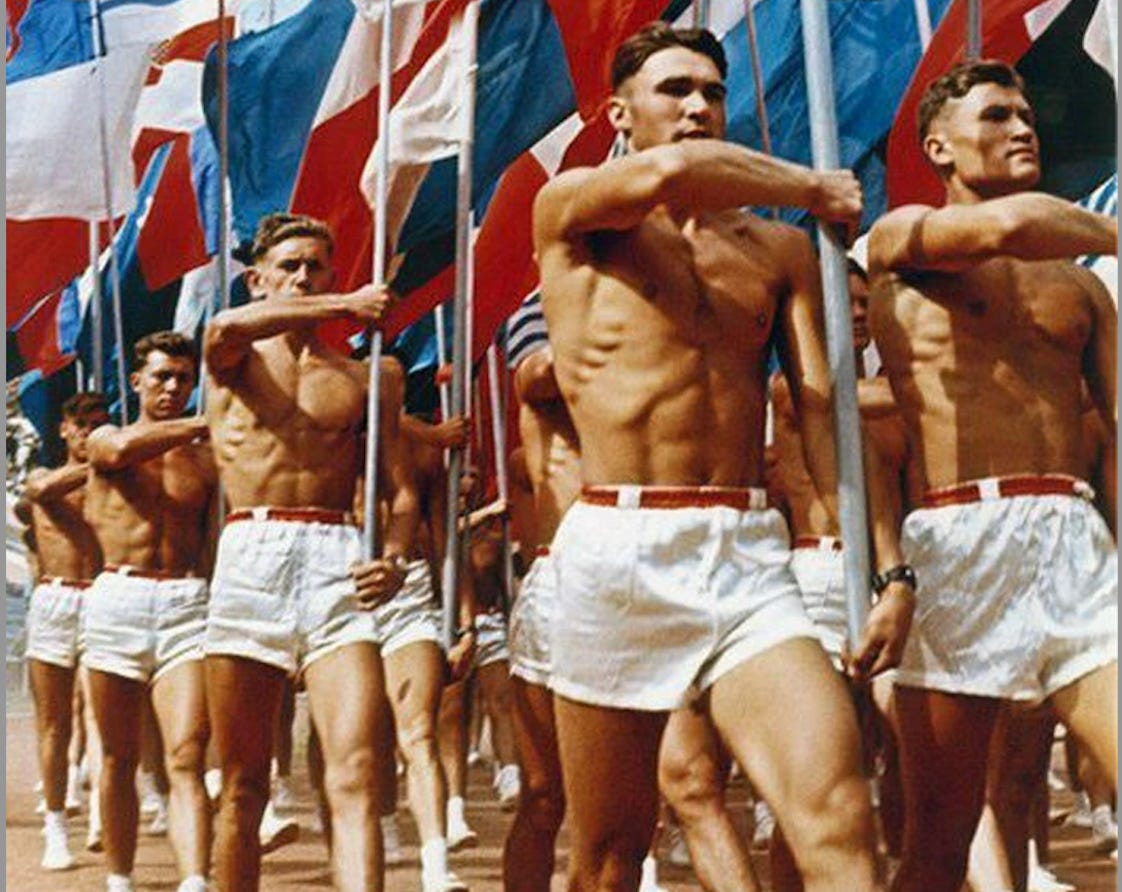

This is a project to “forge a new Adam,” one shed of the old restraints of hierarchy and traditional authority, a journey into the new horizon of man. It’s a chance to participate in a total civilizational redesign, an attractive prospect for many and one that, as Vasily confesses, veers into the religious.

It’s so potent a conversion that on his death, years after the fall of communism in Russia, he leaves his apartment to the Party in his will and not his grandson, who cares for him in his old age.

Yet, in its attempts to radically remold man there are persistent hints of how communism operates in the shadow of far more ancient paradigms. Perhaps it’s why communism seems so often to require top-down authoritarianism and ruthless snitching to enforce the utopia. (You WILL own nothing and You ARE happy, comrade!)

Earlier in the interview Vasily recalls: “We’d have komosol weddings. No candles, no wreaths. No long hair, she cut it all off before the wedding. We hated beauty.”

Of course, I thought, because you can’t redistribute beauty’s power. Intelligence can be put to work for the common good. Athleticism too. Even charisma. And, all those characteristics are fortified by hard work. Beauty, though, is selfishly personal. It can’t be spread out among the masses. The genuinely beautiful don’t even need to do anything to earn its benefits. It’s bestowed by God, by nature, by the fateful colliding of genes, outside Party control.

You can always try to enforce mass hideousness, Harrison Bergeron style. Even that scenario fails. The most attractive ballerina can then be picked out because of how much she’s been modified:

She must have been extraordinarily beautiful, because the mask she wore was hideous. And it was easy to see that she was the strongest and most graceful of all the dancers, for her handicap bags were as big as those worn by two-hundred pound men.

The infuriating power of beauty is perfectly illustrated in a different account in Secondhand Time, by a Jewish World War II survivor who notes that the Nazi soldiers who passed through their villages would kill all their farm animals, except for the most beautiful horses.

THE PROBLEM WITH PROGRESS

On drives to and from the beach, I read aloud to Sam. We’ve gone through a surprising number of books this way, including Moby Dick, Lonesome Dove, a large number of books on aliens, and 1/2 of Gravity’s Rainbow.

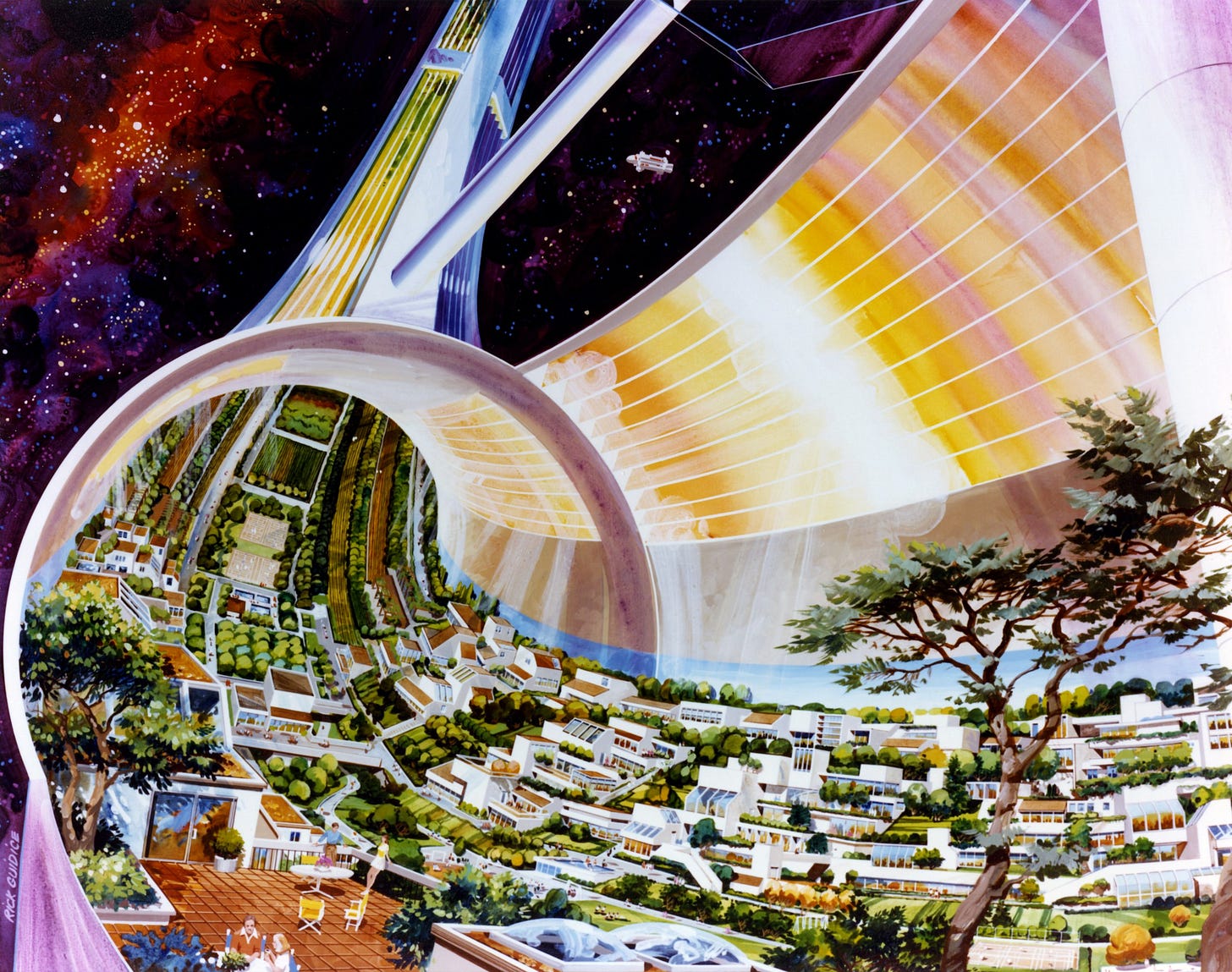

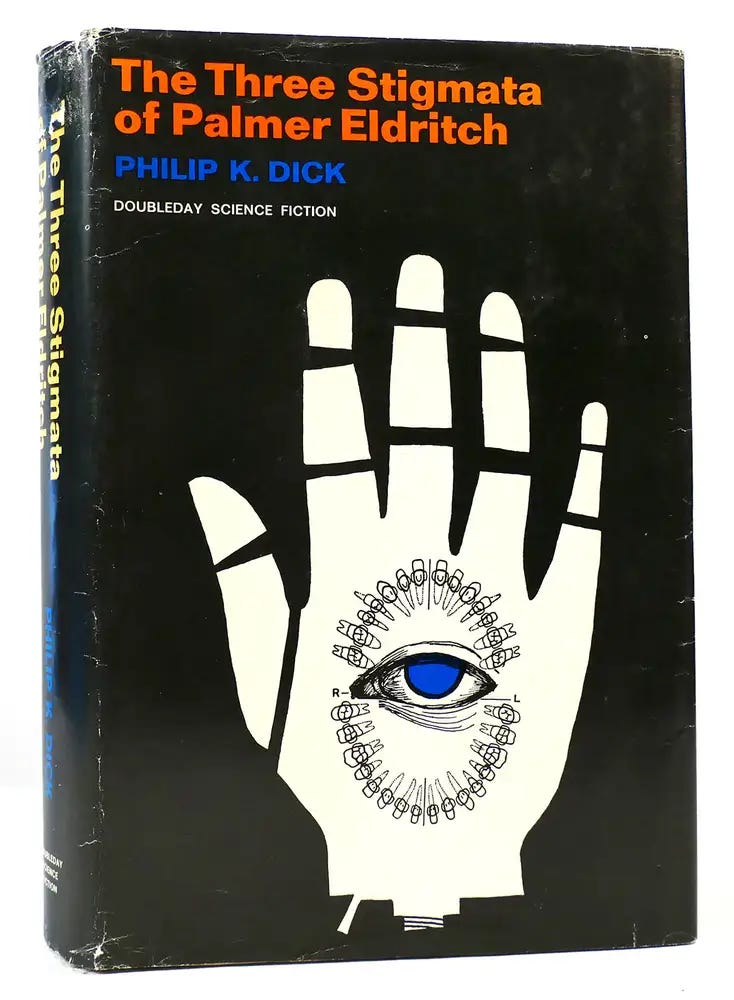

We’ve just finished The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch by Philip K. Dick, which is set in 2016. It’s a world that would appeal to both left-wing and right-wing progressives. Man is colonizing the solar system, with a United Nations in charge. Psychedelics are all the rage. A revolutionary new form of therapy is evolving man into the next iteration of himself.

In this brave new world, however, progress’ promises seem to have largely failed to materialize.

The United Nations is comprised of hyphenated last-name Buddhists (NPR hosts, basically?), who rule imperially over an overheating Earth and a solar system of dreary planet colonies. Turning Mars or Venus into a utopia isn’t of interest to the common people. Earthlings must be forced into off-planet exile to man these outposts. To alleviate their misery, they’ve taken to ingesting a psychedelic substance called “CAN-D,” grown and sold (illegally) by the P.P. Layouts company.

Psychedelics aren’t vaulting them into new heights of creativity or awareness, though. On CAN-D, they simply gaze down at miniature dollhouses (also peddled by the obliging P.P. Layouts company) and hallucinate into a cheery, Barbie dream-land of bygone Americana. They drive convertibles, swim in the ocean, or flirt over cocktails via blonde “Perky Pat” or her male companion Walt.

P.P. Layouts’ booming business model is soon threatened by the return of industrialist Palmer Eldritch, after 10 years in far-flung space, rumored to be carrying a new, far more powerful psychedelic. Unlike the restrictive, experience of Can-D in Perky-Pat land, Chew-Z offers infinite variety. Each chewer can go wherever they may desire, to do as they please, in a grand expanse of exploration.

Ironically, however, this is even worse. The prescribed P.P. Land is, at least, a shared one. Men and women dose simultaneously and play together as miniaturized Pat or Walt. If there’s only one layout for a group, multiple people share Pat or Walt’s body and make collective decisions.

Chew-Z, however, thrusts man away from communal reality. Chewers wander alone in their separate hallucinations, talking to only empty avatars and experiencing nothing that is shared with another. It’s like those horrifying experiences of becoming conscious within a dream, knowing it’s a mirage, and yet you can’t get yourself to awaken.

PKD seemed to have intuited, even at this early stage of the psychedelic revolution of the 1960s, how much these substances were, essentially, vehicles for individualism. Hallucinogenics may send us on a cosmic trip but it is always a solo excursion, no matter how many people also report seeing “machine elves” or divine snakes in the next dimension.

Substances aren’t even required to forge this bleak isolation. Postmodernism, in which all truth has become relative and “culture-bound”, has largely obliterated communal reality. In the post-internet world, it’s our physicality which is the delusion and mental fantasy the truth. Online, no one knows you’re a dog (or a man).

Palmer Eldritch and his Chew-Z are described as “…the evil, negative trinity of alienation, blurred reality and despair.” He embodies this stigmata of misery, with a robotic arm, mechanical eyes and gnashing metal teeth. Body mods aren’t revolutionizing

man, they’re merely distancing him from the sensual world.

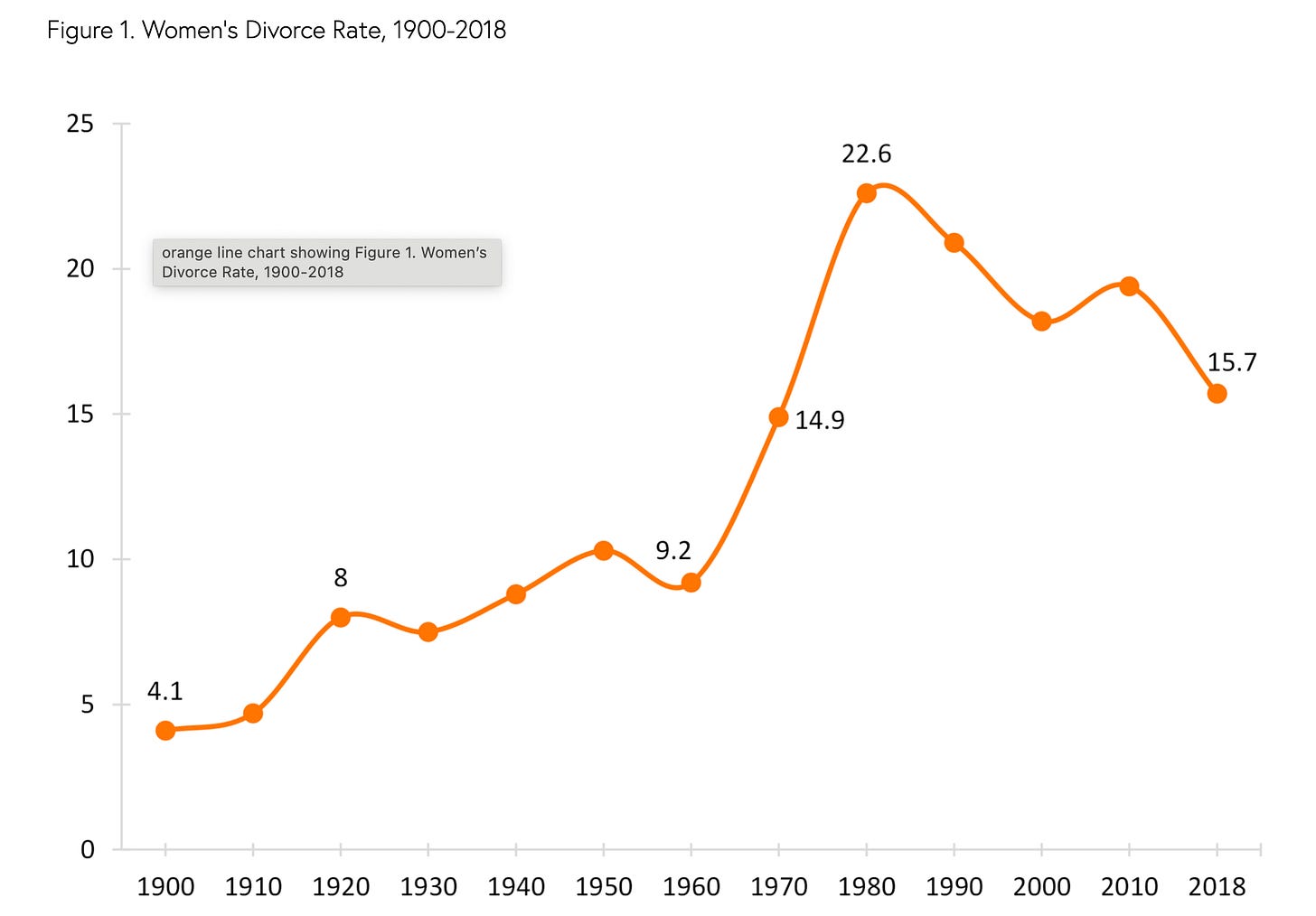

It’s not just psychedelics that PKD feels some despair over. We get a rare look at divorce regret, from an era when Americans were at the cusp of widespread marital breakdown. Between 1960 and 1980, the divorce rate nearly doubled in the U.S. You hardly ever see men of this era lamenting their separations, which is perhaps why this is so striking a read.

The book’s central character is Barney Mayerson, P.P. Layouts’s psychic buyer. Before the story begins, Mayerson divorces his ceramicist wife Emily in order to move up in life. She had gotten pregnant, which would have prevented a move to a nicer apartment and hampered his job prospects. Out goes Emily, in goes bachelor life swilling martinis and seducing secretaries. The book opens upon Barney coming to, after a boozy night with a female coworker.

Eventually, Mayerson begins to regret this decision. After he’s fired from P.P. Layouts, he realizes that career aspirations tricked him into throwing away the one thing of actual substance in his life.

Both in the physical world, and on the psychedelic plane, Mayerson starts trying to win Emily back (or prevent himself from divorcing her). He endangers his life with a second dose of Chew-Z just so he can right things, even if only in a hallucination.

Mayerson’s torment has a poignant desperation:

“If I can reach Emily before the divorce, before Richard Hnatt [Emily’s second husband] shows up — as I first did, he thought. That’s the only place I have any real chance. Again and again, he thought. Try! Until I’m successful.”

PKD may have been writing from “lived experience” as they say. The novel was written around 1963, coinciding with the collapse of PKD’s second marriage to Anne Rubenstein.

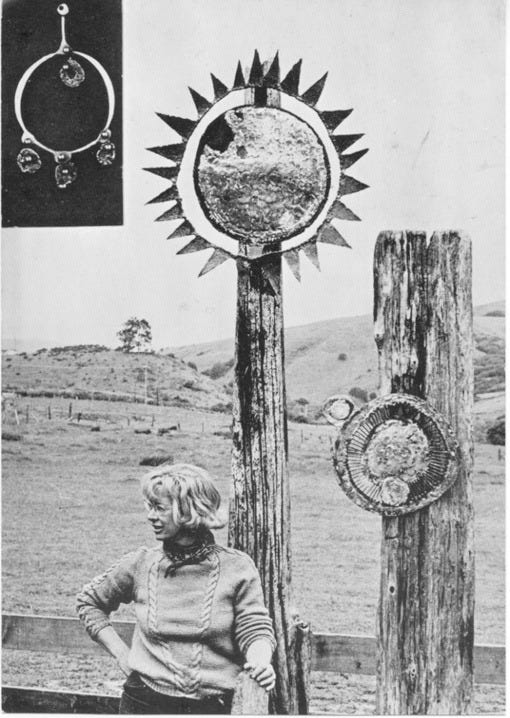

The two were together between 1958 and 1965, caring for her children and their daughter alongside flocks of farm animals in bucolic Point Reyes, California. Although it was a tempestuous union, it’s also been described as PKD’s most “domestic” and productive period. He wrote prolifically during this time and completed The Man in the High Castle, his only work to win a Hugo Award.

The marriage dissolved after PKD accused Anne of trying to kill him, and had her committed to a mental institution. His accusation was most likely a paranoid delusion due to the prescription methamphetamine PKD was increasingly consuming in order to churn out enough writing to support the family. He never achieved success in larger publishing houses during his lifetime and had to rely on the smaller dollars offered by sci-fi magazines and presses.

After two weeks confinement in the hospital, Anne returned home, PKD went to live with his mother, and they soon divorced.

It seems quite probable that Mayerson and Emily’s troubled relationship mirrored Dick’s own. Anne was even an artist like Emily. Her modernist jewelry designs sold well after the divorce, just as Emily’s ceramic designs take off in PKD’s fictional world.

After the divorce with Anne, things continued to spiral for PKD. His drug use intensified. He had multiple suicide attempts. He eventually had a serious break with shared reality, a quasi-religious one sparked by staring into the golden fish necklace of a woman dropping off medications after PKD’s wisdom tooth removal surgery. He died quite young, at only 52.

Like psychedelics, PKD seemed to have sensed something deeply awry in divorce or at least sensed its potential for misery (although, of course, who knows if saving this marriage would have prevented any of his later mental problems.)

Even therapy seems a false promise in PKD’s 2016.

The wealthy indulge in “e-therapy” or evolution therapy, administered by sinister German doctors. The therapy boosts your intelligence (if it doesn’t backfire and make you stupider) but each subsequent round also enlarges your head. Those who partake are disparagingly called “bubble heads.” The elite, of course, carry on with the evolution because not doing so means “falling behind.” To keep up with the Joneses, therefore, one must evolve into a laughable mutant.

Mayerson eventually winds up on Mars, living among the colonists who favor afternoons slumped over on drugs rather than homesteading. He begins a garden plot in the desert of Mars, vows to avoid psychedelics, and sets out to “cleanse” himself of the mark of Chew-Z. It’s a strangely ascetic end:

“Maybe there are methods to restore one to the original condition — dimly remembered such as it were — before the late and more acute contamination set it. He tried to remember but he knew so little about Neo-Christianity. Anyhow, it was worth a try; it suggested there might be hope, and he was going to need that in the years ahead.”

PKD seems in agreement with Pascal, who wrote:

“The only thing which consoles us for our miseries is diversion, and yet this is the greatest of our miseries. For it is this which principally hinders us from reflecting upon ourselves, and which makes us insensibly ruin ourselves. Without this we should be in a state of weariness, and this weariness would spur us to seek a more solid means of escaping from it. But diversion amuses us, and leads us unconsciously to death.”

Then again, the book also ends unclear if we ever even left the nightmarish Chew-Z world to begin with, once the first dose is consumed at the mid-point of the story. For Dick, it seems, the ultimate horror may not be progress’ problems, but that progress can’t actually ever be stopped.

As always, please share what you’re reading in the comments!

Reading (not as diligently as I could be) Orhan Pamuk's Istanbul: Memories and the City, which is both a history of the city/the late Ottoman Empire and a memoir. I definitely need to move up my copy of Alexievich's Voices from Chernobyl on my to-read list.