The true origins of yoga

In which we trace the starting points of yoga as exercise, which are decidedly not what they might seem...

I recently read a comment on the internet about tech bros’ propensity for pushing supposedly “ancient” eastern religious practices onto the masses, things like mindfulness and yoga, despite (per the commenter) the fact that yoga is “an invention of the 20th century.”

This gave me pause. Like most Americans, I think, I had imagined yoga to be an old practice brought from India to the New World in the early 20th century by gurus steeped in time-honored tradition.

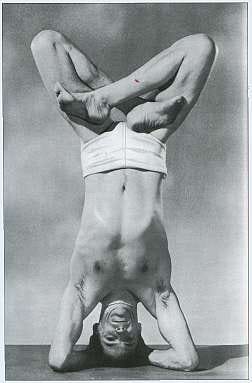

I actually even have a small personal connection to this early era of American yoga. My father’s great cousin, Theos Bernard, was one of the first white men to promote yoga in the United States. He published the seminal book Hatha Yoga: The Report of A Personal Experience in 1943 which detailed his tutelage under an Indian guru. It contains some of the first photos of an American man conducting yoga, and introduced many of his countrymen to the practice.

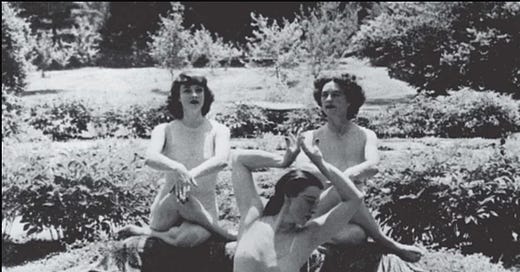

Theos’ uncle Pierre Bernard was even more instrumental to the “Americanizing” of yoga as Theos. Pierre Bernard, or “the Magnificent Oom” as he was later branded, studied meditation under a Tantric yogi in Nebraska and eventually became a famous yogi himself, as well as a philosopher and semi-cult figure in New York. His immense Hudson Valley estate introduced hundreds of New York City’s wealthy, elite women to the (often sexual) joys of stretching.

I imagined that this was the standard path for yoga: wise teachings from the East were popularized (and bastardized) by American bohemians, hippies, health nuts, and tech bros.

This is actually not remotely correct. Exercise yoga’s clearest origins lie in Danish gymnastics, not in grizzled Indian gurus. There is an entire fascinating book by Mark Singleton on the subject, Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice which I highly recommend and from which I’ve extracted a considerable amount of knowledge.

When I posted about some of this on Instagram, I had a large number of people who were also surprised by this discovery. I thought I’d lay out a brief history of yoga’s intersection with gymnastics, as well as the influences of body-building, emergent Indian nationalism and, sort of, Nazis.

(To preface, I am not a yogi nor a yogi scholar and I am also a blonde so please feel free to conduct your own research.)

First, we have to make a distinction between yoga as a spiritual practice and yoga as an exercise practice. Yoga as a spiritual practice within Hinduism has existed in India since (depending on which theory you believe) somewhere between 1,000 or 200 BCE. Whatever the precise century, that’s an exceptionally long time ago.

Yoga, and its many sub-branches and schools of thought, is a practice, philosophy, ethics system, and means to spiritual awareness/enlightenment. Ancient practitioners would have little idea of what to do with a yoga mat other than to sit on it and meditate, however.

A tradition of poses called “asanas” which are a part of the Hatha yoga tradition, do look like today’s exercise yoga. However, these were meditation poses to be held for long periods of time. The idea that one did this to tone up the body would have been rather confusing to past Hatha yogis.

The aforementioned Pierre Bernard’s own training in Hatha yoga was not physical, but mental. He initially got noticed for the ability to launch himself into trance states so profound, he could tolerate surgical needles pushed deep into his body.

So, to be clear, I am referring to exercise yoga (intended to strengthen the body), not the fairly sedentary spiritual practice, when I say yoga is an invention of the 20th century.

With this cleared up, we can talk about how yoga as an exercise practice began. We should start specifically with an important German book published in 1793 by Johann Christoph Friedrich GutsMuths.

GutsMuths was deeply concerned about the weakening of German bodies and minds by the urbanization arising from the industrial revolution. Instead of striding teutonically around nature, these new urbanites were now stuck at desks shuffling paper.

Rejuvenating German masculinity was of primary importance to him. The key to this, thought GutsMuths, was healthy exercise. His book Gymnastics for Youth outlined around 30 exercises, from jumping to throwing objects, that could strengthen the body in rigorous and “natural” ways. It was, essentially, the first modern training manual for gymnastics teachers.

An excerpt from Gymnastics for Youth is nearly indistinguishable from modern rhetoric around tech neck and coddled, indoorsy Millennials and Zoomers:

“Many can discern a man’s occupation in the figure of his body: men of sedentary employment appear half sitting even when they walk, and are strikingly distinguishable from those, whose business requires various bodily exertions. Such people are seldom adroit at any thing, in which their own tools, and their own manual arts, are not required. They are easily terrified at every little danger, because they know not how to succor themselves. This is still more true of people of higher classes, because they are more tenderly brought up, and unused to bodily exertions.”

Much of GutMuths movements replicated ancient Greek gymnastics, which had been slumbering in a long hiatus, but GutsMuths was also influenced by the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s then-revolutionary “return to nature” ethos. GutMuths mixed in a scrappy, outdoorsy frolic component to his exercise routines as well.

GutsMuths brought a new philosophy to exercise. Sports were then primarily class-segregated — fencing or riding for aristocrats, military drills for the middle class, manual labor for the lowest. He believed that exercise should not just be the byproduct of producing physical objects or siloed into genteel sports, but for building up the power of the individual. His program could be used by almost anyone, with minimal equipment.

His book had an enduring influence across Europe. Franz Nachtegall read it and was inspired to teach gymnastics in Denmark, eventually training the Danish Army. A Swede, Peter Ling, also read GutMachs and studied Nachtegall’s regime which he credited with restoring his health after a tuberculosis diagnosis.

Ling trained enrollees at the Military Academy at Carlsberg and eventually opened the Swedish School of Sport and Health Sciences, the oldest school in the world focused on physical education.

Niels Bukh learned Ling’s regime and then developed his own, recorded in his 1924 book Primary Gymnastics or Primitive Gymnastics. This book is probably the truest origin point for exercise yoga. A glance at any of the poses pictured in it, and you’ll recognize what attendees at the local namaste center in your hipster neighborhood are doing at 8am.

Ling’s and Bukh’s gymnastics spread to India in the early part of the 20th century, primarily through the efforts of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) which set up shop in India under Britain’s rule. The American H.C. Buck, a YMCA leader, founder of the first college of physical education in India and trainer of India’s first Olympic team, eagerly promoted gymnastics at YMCA facilities.

Buck blended these rhythmic Danish gymnastics with some of those pre-existing traditional asana poses to offer the “best of the East and West” to his pupils. Bukhs and Ling gymnastics soon became the two most popular fitness regimes across India.

There was one other important influence from Europe: the showman and body-builder Eugen Sandov. Sandov was already a global sensation when he landed in India for a tour in 1905. He’d kicked off the modern era of body-building by displaying bulging muscles precisely toned to match those on ancient Greek statuary. What was previously thought to be an unattainable physical ideal now seemed possible to the common man.

When Sandov arrived in India, thousands crowded into massive tents and theaters to watch him pose and to listen to him extol quasi-spiritual lectures on the importance of toning the body. Some paid extra to go back stage to squeeze his muscles.

For eager Indian attendees, ruled by foreign colonizers who regarded them as physically inferior and effeminate, Sandov’s messages of body-building were refreshingly free of racial restrictions. “The native Indians have a foundation for the building of large physical men,’” he insisted, “it is only because of their lack of proper food and systematic exercise that they are thin and haggard.”

With Sandov’s techniques, Indian men felt they had finally found a way to match the physical prowess of Europeans. This sentiment melded well with India’s emergent independence movement, which was hoping to wrest power back from the British crown. Like nearly all independence movements, strengthening the body of the individual citizen had become increasingly crucial. The robust could fight back; but the weak were easily cowed.

Thus, already popular gymnastics and strength-training routines (infused now with some ancient yogic terminology) became a tool for empowering the Indian people. Gurus and liberationists around the country enthusiastically adopted this new ideology. Freedom-fighting yogis roamed the land, agitating for independence. while dispensing body-building advice instead of spiritual guidance.

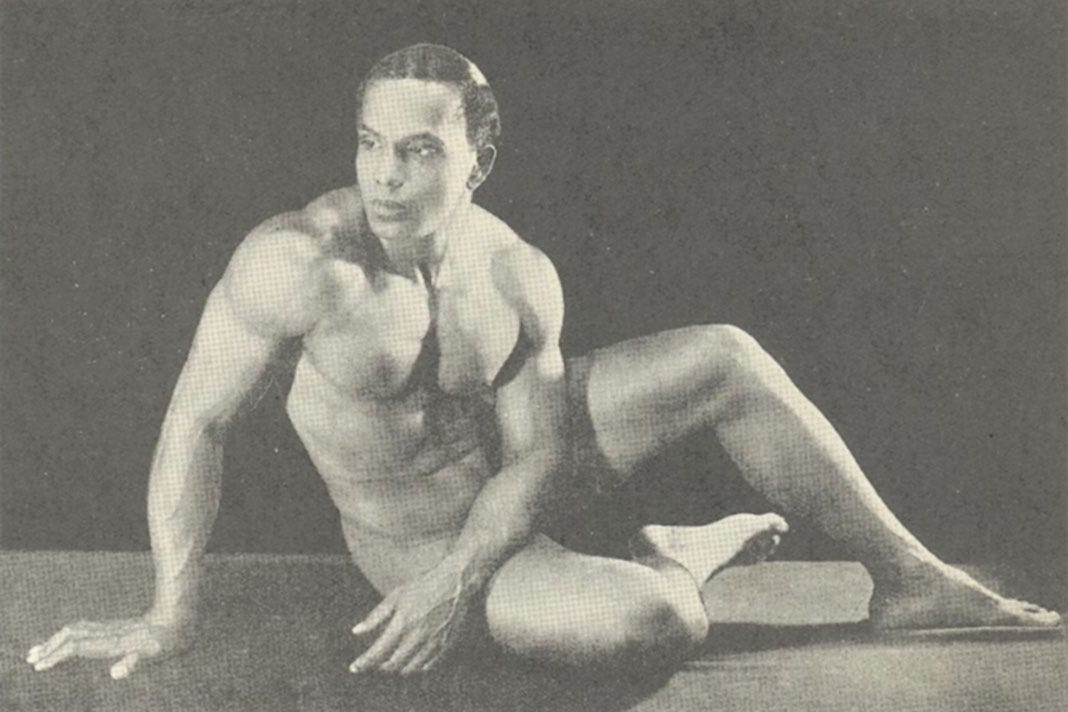

Exercise yoga’s popularity was also forged by a nationalist desire to breed a stronger Indian race, a concern universally popular during this high point of the eugenics movement. The famed Indian bodybuilder who promoted exercise yoga, K.V Iyer, wrote in 1927: “Physically deficient mothers and devitalized fathers [produce] helpless derelicts and weaklings.”

India’s coupling of physical fitness with nationalist impulses wasn’t unique.

German gymnastics enthusiast Friedrich Ludwig Jahn (1778-1852) refined GutsMuths techniques and invented many of the most familiar gymnastics routines: the parallel bars, the rings, the balance beam, the horse.

During Jahn’s time, Napoleon’s army occupied much of Germany. France’s military force and cultural influence was, to Jahn, smothering his homeland. He felt that Germans needed some sort of training that would build them up physically and morally so that they could eventually liberate the homeland.

Jahn opened a gym, Turnverein, that promoted his training system and launched the populist movement dubbed the “Turners”. He coupled his gymnastics courses with nationalist writing and advocacy for freedom from France’s occupying forces and a unification of Germany. These activities got him arrested and, at one point, banned from living near schools for fear of his influence over young people.

After participating in the failed 1848 uprisings, which promoted a unified Germany in opposition to the aristocratically run confederation of states, many of his followers fled the country. Some, like Charles Follen, landed in America. Follen’s Turner ethos found expression through radical abolitionism, which eventually got him fired from Harvard.

Some scholars argue that Jahn’s writings and his promotion of a German identity were foundational to the later Volksisch ideology of the Nazis (who also believed that rigorous, outdoor training of the body was a vital part of returning the German people to their prime.)

There’s actually a somewhat direct connection between gymnastics and Nazism. Bukh’s work-outs became as popular in Germany as they were in India, and he eventually aligned himself with the Nazi Party (much to the chagrin of the Danish after the Nazi invasion of Denmark).

A mass gymnastics display complete with Nazi flags in Berlin in 1933 was performed using Bukh’s movements. There were, no doubt, Indians several thousand miles again conducting the same routines under the auspices of their own nationalist movements.

Much of this origin story is now totally obscured by the clouds of time as well as by savvy myth-making. You’re much more likely to see yogis or journalists accuse white yoga participants of “cultural appropriation” than to see them question why Indians are doing Danish work-outs. Perhaps, it’s partly because removing the mystical narrative of ancient India would wipe away much of yoga’s appeal to its new-age customer base.

Even my own distant relative glamorized his path to yoga as well. His later biographer revealed that Bernard almost certainly fibbed about the Indian guru and was actually taught Hatha yoga by his father.

I love your writing!